Lancastria: Una tragedia dimenticata

di Tealdo Tealdi

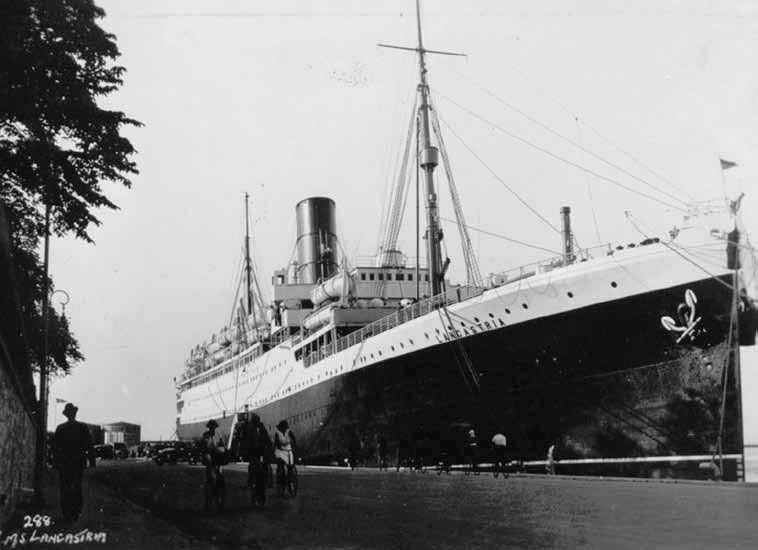

LANCASTRIA. Nessuno ricorda questa nave da crociera varata nel 1922, requisita nel 1940 per il trasporto delle truppe.

LANCASTRIA. Nessuno ricorda questa nave da crociera varata nel 1922, requisita nel 1940 per il trasporto delle truppe.

Affondata appena salpata da Saint Nazaire carica di soldati inglesi in ritirata dal fronte francese, si inabissò portando con sé più di 4000 persone.

Ma sul dramma fu mantenuto un assordante silenzio. Complice la guerra e la ragion di Stato.

Ci sono molte tragedie che hanno avuto come teatro il mare, ma nessuna paragonabile a quella della nave passeggeri Lancastria affondata quando era carica di soldati, in soli 20 minuti, il 17 giugno 1940. Ancora oggi nessuno sa se la stima di 4000 morti sia davvero esatta. Tutti hanno in mente il Titanic, con i suoi 1500 morti.

Noi italiani non possiamo dimenticare i 55 che morirono nell’affondamento dell’Andrea Doria in tempo di pace o il disastro della corazzata Roma, colpita da aerei tedeschi il 9 settembre 1943 con 1393 perdite (si veda Arte Navale 59), ma la fine del Lancastria pochi la ricordano.

La nave ancorata nella baia di Villefranche, vicino al Principato di Monaco. Come nave da crociera, non più impegnata nella rotta attraverso l’Atlantico la Lancastria subì alcune modifiche. Le classi, per esempio vennero ridotte a due.

Eppure è il più luttuoso evento singolo nella storia della Marina inglese e, in assoluto, una delle più grandi tragedie marittime. Le ragioni di questo incredibile silenzio vengono da lontano e sono anch’esse parte della Storia con la S maiuscola.

Eppure è il più luttuoso evento singolo nella storia della Marina inglese e, in assoluto, una delle più grandi tragedie marittime. Le ragioni di questo incredibile silenzio vengono da lontano e sono anch’esse parte della Storia con la S maiuscola.

Non è un caso infatti che a tener vivo il ricordo di questa tragedia sia solo la perseveranza dei sopravvissuti rimasti (al momento attuale solo 70) e dei loro discendenti. Si può veramente affermare che i suoi caduti siano morti due volte: la prima per l’attacco dei bombardieri tedeschi, la seconda per la ragion di Stato.

Ne raccontiamo la storia per dare anche noi un piccolo contributo alla sua memoria.

La Seconda Guerra Mondiale in Francia era stata disastrosa per le truppe alleate, ma per fortuna l’Operazione Dynamo era riuscita a salvare 340.000 soldati tra il 27 maggio e il 4 giugno, recuperandoli da Dunkirk/Dunkerque: “Un vero miracolo”, commentò Winston Churchill, anche se sulle 861 navi di tutte le dimensioni, che parteciparono al salvataggio, ben 243 affondarono.

Sopra: ricco buffet sul ponte della nave durante una crociera nel Mediterraneo.

Erano rimasti comunque ancora 200.000 soldati sul suolo francese, che non avrebbero avuto scampo; per salvarli fu intrapresa l’Operazione Ariel, che ne prevedeva l’evacuazione via mare attraverso diversi porti, tra cui Saint Nazaire. Tra le navi preposte a questo scopo c’era il HMS Lancastria che, dopo aver lasciato il 14 giugno Liverpool al comando del Capitano Rudolph Sharp, era arrivata nell’estuario della Loira il 16. La nave imbarcò sia soldati che civili, per la maggioranza britannici, canadesi, australiani, neozelandesi, polacchi, belgi e personale della Raf.

Il numero delle persone presenti a bordo era compreso tra le 6.000 e le 9.000 persone, a fronte di una capacità ufficiale di 2.200, inclusi i 325 uomini d’equipaggio.

Il Lancastria partì da Saint Nazaire con il suo carico umano il 17 giugno, il giorno prima dell’appello del generale Charles De Gaulle a tutti i francesi restati fedeli alla Repubblica e tre giorni dopo l’ingresso delle truppe naziste a Parigi. Alle 15.48 di quello stesso giorno, 9 miglia dalla costa francese, la nave fu attaccata da una squadriglia di Junkers J88 e colpita da diverse bombe.

Affondò in una ventina di minuti. Le vittime ufficiali furono circa 3.500, ma il numero esatto non è sicuro, e si pensa, con fondatezza, che potrebbero essere state anche più di 4.000.

Locandine per la promozione delle crociere sul Lancastria. La nave della Cunard Line era entrata in servizio nel 1922 con il nome Tyrrhenia cambiato due anni dopo per la difficoltà dei passeggeri nel pronunciarlo. Poteva portare 2200 persone oltre ai 325 membri dell’equipaggio.

La nave Lancastria in breve

| Varo: | 1920 |

| Cantiere navale: | W. Beardmore, Glasgow |

| Società: | Cunard Line |

| Nome: | Tyrrhenia cambiato in Lancastria nel 1924. |

| In servizio: | 19 giugno 1922 nella tratta Glasgow-Montreal |

| Lunghezza: | 168 mt |

| Pescaggio: | 21,25 mt |

| Stazza: | 16.243 ton |

| Propulsione: | turbine a vapore Brunes-Curtiss |

| Potenza: | 13.500 cv |

| Velocità: | 17 nodi |

| Equipaggio: | 325 persone |

| Passeggeri: | 2200 |

| Classi: | 3, 2 dal 1924 |

| Rotte: | Liverpool-New York fino al 1932 poi nave da Crociera nel Mediterraneo. Nel 1940 fu requisita per il trasporto truppe. |

| Bandiera: | Regno Unito |

Oltre 1.400 tonnellate di carburante si riversarono in mare, creando una macchia nera spessa, in certi punti, fino a 60 centimetri che prese fuoco e rese molto difficile anche agli esperti, salvarsi a nuoto. Dei naufraghi, mitragliati in acqua dagli aerei nazisti, si salvarono 2.500 persone, in gran parte grazie ai bretoni di Saint Nazaire e di altre località costiere. A lungo la notizia di quella immane tragedia fu nota solo in Bretagna. Ogni informazione sull’avvenuto affondamento, da parte dei sopravvissuti o dei militari, fu infatti proibita ufficialmente sotto pena di corte marziale.

Qualcosa però trapelò: il New York Times e lo Scotsman lanciarono la notizia il 26 luglio 1940, ripresa dal Daily Herald lo stesso giorno e dal Sunday Express il 4 agosto, che pubblicò anche una fotografia della nave rovesciata.

Winston Churchill disse più tardi:

Quando seppi dell’accaduto ne vietai la pubblicazione, in quanto i giornali avevano già troppe notizie disastrose per quel giorno. Volevo poi togliere il divieto dopo pochi giorni, ma gli eventi si susseguivano così velocemente, che me ne dimenticai.

Ma come fa notare il giornalista James Kirkup (suo nonno si salvò perché non riuscì a salire a bordo a causa del sovraffollamento della nave), non poteva essere solo una dimenticanza: l’eventuale notizia della strage avrebbe infatti messo in ombra il “miracoloso” salvataggio Dunkirk, portato a termine da piccole navi e con grande eroismo.

Quella drammatica evacuazione di soldati, soprattutto inglesi, era diventata il simbolo potente di come questo popolo, proprio di fronte alle difficoltà, fosse capace di reagire e riprendersi. Nulla doveva intaccarne l’effetto positivo sul morale del Paese.

Con gli anni tuttavia la verità avrebbe dovuto venire a galla in tutta la sua tragica importanza. Invece ancora oggi il governo di Sua Maestà Britannica si rifiuta di trasformare il sito marino dell’affondamento in tomba di guerra, sostenendo che si tratta di acque territoriali francesi. Nel luglio 2007 è stata presentata una richiesta in tale senso, regolarmente respinta.

Il 17 giugno del 2005, sessantacinque anni dopo l’affondamento del Lancastria, la campana di bordo è ricomparsa, nel cimitero francese di La Baule, mentre una delegazione britannica della Lancastria Association (www.lancastria-association.org.uk) vi si era riunita per commemorare l’evento; prima di allora non era mai stata vista, nonostante le voci sul suo recupero.

Su di essa compare ancora il vecchio nome della nave che la Cunard Lines aveva battezzato Tyrrhenia. Nome cambiato in Lancastria perché i viaggiatori avevano difficoltà a pronunciare il precedente. La campana era stata sistemata sui gradoni del sacrario da un anonimo che ha lasciato un biglietto, spiegando che lui stesso l’aveva rimossa dal relitto oltre trent’anni prima.

Ora il cimelio si trova a Londra. Al momento attuale solamente il Parlamento Scozzese ha onorato i caduti, con una medaglia disegnata da Mark Hirst, nipote di Walter Hirst, che riuscì a salvarsi dal naufragio. A bordo della nave erano difatti molto numerosi gli scozzesi dell’Expeditionary Corps e questo spiega anche perché la notizia dell’affondamento sia trapelata originariamente in Scozia.

Sul retro della medaglia è inciso:

In riconoscenza per l’estremo sacrificio delle 4.000 vittime del peggior disastro marittimo britannico e per la costanza dei sopravvissuti. Noi li ricorderemo

English

LANCASTRIA. A forgotten tragedy

Many tragedies have had the sea as their backdrop but none is comparable to that of the passenger ship Lancastria, which sunk full of soldiers, in only 20 minutes, on June 17, 1940. Even today, nobody knows if the estimate of 4000 dead is really exact.

Everybody remembers the Titanic, with its 1500 victims. Italians cannot forget the 55 people who died when the Andrea Doria sank in peacetime or the disaster of the battleship Roma, hit by German planes on September 9, 1943 with 1393 lives lost (see Arte Navale 59), but few people remember the end of the Lancastria, although it is the most tragic event in the history of the British Navy and, in absolute, one of the greatest maritime disasters ever.

The reasons for this incredible silence come from afar and are part of History with a capital “H”. Not surprisingly, it is only through the perseverance of the remaining survivors (at present there are only 70 left) and their descendants that the memory of this tragedy is still alive. The victims can truly be said to have died twice: the first time under the attack of German bombers, the second time for reasons of State. We want to tell the story so that we too can make our small contribution to the memory of this tragedy.

World War II in France had been disastrous for the Allied troops, but luckily Operation Dynamo had been able to save 340,000 soldiers between May 27 and June 4, evacuating them from Dunkirk: “A miracle of deliverance,” commented Winston Churchill, even though out of the 861 vessels of all sizes that took part in the rescue operation, 243 sank. Two hundred thousand soldiers were still left on French soil and there would have been no hope for them, but Operation Ariel was launched, to rescue them, evacuating them by sea from different ports, including Saint Nazaire.

The ships requisitioned for this included HMT Lancastria which, after having left Liverpool on June 14 under the command of Captain Rudolph Sharp, had arrived in the Loire estuary on June 16. The ship took on board both soldiers and civilians who were mostly British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealanders, Poles, Belgians and RAF personnel. The number of people on board was between 6,000 and 9,000, against an official capacity of 2,200 including the 325 members of crew. HMT Lancastria left Saint Nazaire with her human cargo on June 17, the day before General Charles De Gaulle’s appeal to all the French who had remained loyal to the Republic and three days after the Nazi troops entered Paris. At 3.48 p.m. the same day, 9 miles off the French coast, the ship was attacked by a squadron of Junkers J88 and hit by several bombs. She sank in about twenty minutes.

The official number of victims was 3,500 but the exact number is not certain and there are grounds to believe that more than 4,000 lives were lost. Over 1,400 tons of fuel leaked into the sea, creating a black oil slick up to 24 inches thick in some points, which caught fire and made it very difficult, even for expert swimmers, to survive. In the sea, the victims were strafed by Nazi planes and 2,500 people survived, to a great extent thanks to the Bretons of Saint Nazaire and other places along the coast. For a long time, this huge tragedy was known only in Brittany. Disclosing any information on the sinking, by survivors or the military, was officially prohibited, under penalty of court martial.

However, some news leaked out: The New York Times and the Scotsman published the news on July 26, 1940, as did the Daily Herald on the same day and the Sunday Express on August 4, which also published a photo of the capsized ship. Winston Churchill later said: “When this news came to me I forbade the publication saying: “The newspapers have got quite enough disaster for-today at least”.

I had intended to release the news a few days later but events crowded upon us so quickly that I forgot to lift the ban.” As journalist James Kirkup (whose grandfather survived because he was unable to embark since the ship was already overcrowded) points out, it could not only be a question of forgetfulness: Any news of the disaster would have put the “miraculous” Dunkirk rescue, carried out by little ships and with great heroism, in the shade. That dynamic evacuation of soldiers, especially British, had become a powerful symbol of how this people, when faced by difficulty, could react and recover. Nothing was to affect its positive effect on the country’s morale.

The ship in brief |

| Launched in 1920 Shipyard: W. Beardmore, Glasgow Company: Cunard Line Name: Tyrrhenia changed to Lancastria in 1924 Put into service on June 19, 1922 on the Glasgow-Montreal route Length: 553 feet Draft: 69 feet Tonnage: 16.243 ton Propulsion: Brunes-Curtiss steam turbines Power: 13,500 HP Speed: 17 knots Crew: 325 members Passengers: 2200 Classes: 3, 2 from 1924 Routes: Liverpool-New York until 1932, then a cruise liner in the Mediterranean. In 1940, she was requisitioned to transport troops. Flag: United Kingdom |

With the passing of the years however, the truth in all its tragic importance, should have come to the light. Even today, the British government of Her Majesty refuses to transform the marine site of the sinking into a war grave, maintaining that it is in French territorial waters. A request to do so was put forward in July 2007 and rejected.

On June 17, 2005, sixty-five years after the sinking of the Lancastria, the ship’s bell reappeared in the French cemetery of La Baule, whilst a British delegation of the Lancastria Association (www.lancastria-association.org.uk) was meeting there to commemorate the event; it had never been seen before then, despite the rumors that it had been salvaged. It still has the old name of the ship as Cunard Lines had baptized her: Tyrrhenia. This name was changed to Lancastria because passengers found the previous one hard to pronounce.

The bell had been placed on the steps of the graveyard by an anonymous person who left a note, explaining that he had taken it from the wreck more than thirty years earlier. It is now in London. At the present time, only the Scottish Parliament has honored the victims, with a medal designed by Mark Hirst, grandson of Walter Hirst, who was able to survive the sinking. There were many Scots on board the ship amongst the Expeditionary Corps, and this also explains why the news of the sinking originally filtered out in Scotland.

The following words are engraved on the back of the medal:

In recognition of the ultimate sacrifice of the 4000 victims of Britain’s worst ever maritime disaster and the endurance of survivors. We will remember them.

Articolo apparso sul n. 64 di “Arte Navale”, febbraio -marzo 2011 e qui riprodotto p. g. c. dell’autore.

Altomareblu – Tutti i diritti riservati. Note Legali

Lascia un Commento

Vuoi partecipare alla discussione?Sentitevi liberi di contribuire!